Please read the Indonesian edition of this article at the following link: Performans Esion, Si Pengganggu

I HAVE A friend who is very reactive every time she watches something, whether it is watching on her laptop, at the cinema, or in the theatre live. Every now and then, the scenes that she watches will trigger all kinds of reactions: whispering, hand squeezing, slapping, hugging a friend next to her, or unwittingly kicking her laptop. She herself does not like going to the cinema because she often talks and that can anger other audiences. She finds that watching films in the open air – as a little kid, she often watched celebration shows in her neighborhood – is much more exciting than watching films at the cinema. She does not have to sit in silence on those occasions. There would be fewer hisses, Sssttt! directed at her as she talks, which is the kind of reaction that she usually gets at the cinema.

My friend’s habit is not uncommon or weird at all. She was not raised to watch films at the cinema. She has gotten used to watching open-air cinema, village orchestra, and shows hired for local festivities, whose spectatorship is fluid as these shows allow their spectators to interact freely. They are indeed the more dominant shows in the local scene. If we look at some traditional shows such as lenong, ludruk, ketoprak, and other wayang shows, it is apparent that there has long been a fluid stage for the audience and performers to interact. Some comedies, musicals, and talk show programs on TV use this model of staging. Opera van Java (Trans 7, 2008 – now) and Extravaganza (Trans TV, 2004 – 2013) are the examples of the TV shows that use the interaction between host and audience as their main element of entertainment. Perhaps this model of spectatorship is what my friend would choose. In fact, she is not the only one who would think that way.

In the context of spectatorship in Indonesia, it is difficult to attain a sterile space that can guarantee the sacredness of spectacle. In the tradition of film watching at the cinema, for instance, the darkroom, along with minimum noise, is a precondition needed to be satisfied for the spectacle to be sacred. However, the written and spoken rule of watching – which is thought to be able to guarantee that sacredness – must deal with the public who like to talk and whisper to the extent that their sound has taken form as a disruption.

Similar preconditions and its problems also occur in the works focusing on sound. Preventing sound from entering the art space is a sacredness often needed. Yet, this condition could only be actualized when there is enough intensity in making the space sterile by creating a specific suitable space and rule. Still, that is not enough to guarantee the work will be free from any disruptive sound, including, and especially from the noise that the audience will make. For sound or noise art, this particular socio-cultural situation becomes a challenge open to responses.

The first time I encountered such a response was on May 19, 2018, when I saw the performance of Theo Nugraha, a sound artist from East Borneo. Theo’s performance Sinyal Selatan was a result of his one-month residency in Forum Lenteng. He first did a field recording in Forum Lenteng and South Jakarta, which he then relistened and remapped using sketches, symbols, and written words. In his performance in Forum Lenteng, the sounds that he had selected were then composed live and became intertwined with the sounds from his electronic device and the ambiance outside Forum Lenteng. The noise soundscape of the performance caused me to think about the noise pollution in Jakarta.

And Theo responded to me with his premise: the noise in Jakarta was no longer relevant since the city was already too noisy, Forum Lenteng too was filled with so much noise that came from its inhabitants. Hence, he chose to reframe those existed noises.

It does not feel right to call myself a sound art expert, let alone a noise expert. However, is it not the case that everyone should be given an opportunity to express their thoughts on their own experience as a spectator, in order to enrich the discourse and note archives?

Therefore, my writing intends to provide documentation and thoughts of the experience of seeing Milisifilem Anggrek’s noise performance Esion. Initiated by Forum Lenteng, Milisifilem is a platform for audio-visual study and production. As their medium, Milisiflem uses workshops and courses, and their participants are currently grouped into three batches. Anggrek is the name of their third batch and has ten participants in it: Humaedi Onyong, Theo Nugraha, Alifah Melisa, Niskala Utami, I Gede Mika, Erviana Madalina, Taufiqurrahman dan Syahrullah, Maria Deandra dan Pychita Julinanda. On January 10, 2019, Milisifilem Anggrek performed Esion in ARKIPEL Academy 2019 in Bukit Athaya Villa, Puncak, West Java.

In Esion, Milisifilem Anggrek developed and adapted Theo Nugraha’s Sinyal Selatan into a collective performance. The performance focused on the sound of Milisifilem Anggrek’s collective activities in Forum Lenteng. The previously recorded sound was interpreted into a graphic score, which was then played and recomposed live.

Activating the Spectatorship

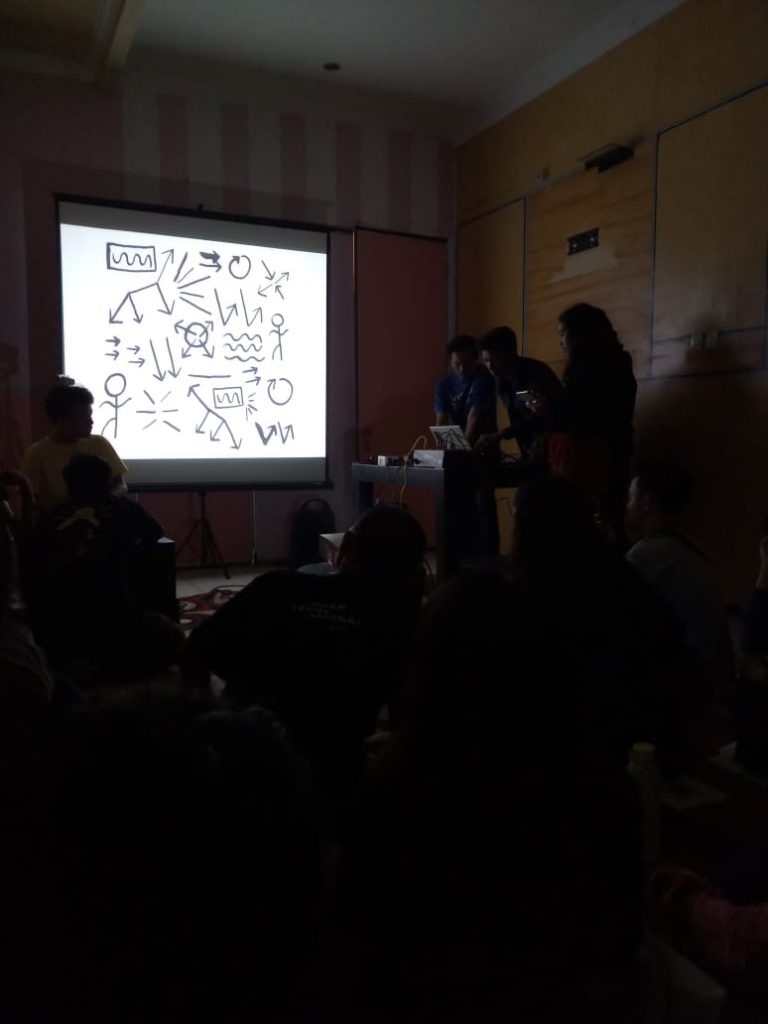

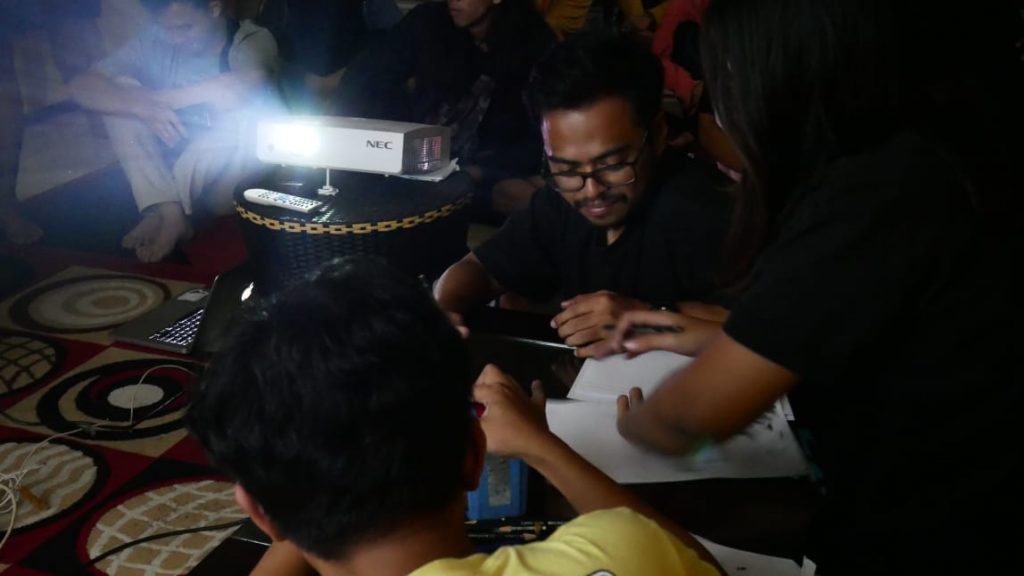

While sitting with my friends from Milisifilem Mawar-Melati (the first and second batches of Milisifilem) and the ARKIPEL Academy 2019 participants, I observed the seven participants of Milisifilem Anggrek who were preparing for their Esion performance. Four people were on the right, and the remaining three were on the left. In the middle, there was a screen with some symbols of sounds and their meanings on it. This symbol glossary was turned into a composition of symbols, which Milisifilem Anggrek named Esion graphic score.

While I was attentively observing, I noticed that the sound of two people laughing behind me became gradually disruptive. I thought, do these two people know that the performance is about to begin, and they were supposed to be quiet by now? Subsequently, I felt confused, why are they sitting behind me when their peers are in front getting ready for their performance?

Their talking persistently disrupted the silence that preceded the performance. The sound started to bother other spectators. They wrinkled their faces, glared, and some of them hissed, Sssttt! at the two girls. Several annoyed spectators told them off. Yet, they continued talking. One spectator, who was sitting in front of me, turned to them and hit them one by one. I was stunned, who knows that someone can react so strongly once the silence is disrupted?

But it seems that the women were not afraid and kept on talking. We soon realized that their noise was part of the performance. They did not only talk and giggle; one of them even asked a spectator for matches. She raised her voice because the noise in front was covering hers, making it difficult for the spectators in the room to hear her evenly. The spectator who she was talking to gave a louder reply. Their acts continued. On one occasion, the woman patted a spectator, initiated a conversation with her, and asked for matches (again). The spectator replied quietly to avoid making any noise, but the woman was talking loudly, which made everybody in the room knew what she talked about. Several spectators laughed at them.

The spectacle space changed from being sterile – in which there was before a perceptible distance between the spectators and the performers – to being very fluid now. The distance was reduced. The presence and the act of the two women became a link and opened the potentiality of interaction within the space. As a link, the women regularly activated the spectators in such a way that the spectators could choose whether they wanted to participate in the sound production, be an active part of the performance, or they could also stay quiet. What usually happens in a performance space is that the spectators are put in a situation where they have limited options, but in this particular space they have more options to engage themselves with. For me, this situation is a critical reflection on the situation of the tradition of watching known as conventions agreed upon by the public: all sacred and quiet.

Disrupting the Established

In Esion, the sound was divided into two parts: the one produced by the electronic speaker and the other produced by the performers and the spectators. The symbols in Esion graphic score were displayed on the screen during the performance, which helped me and the others in remapping the sounds we heard in the space.

But the Esion graphic score did not try to stir its spectators to read its work a certain way. Its readers were free to interpret the sounds that were being composed. In other words, each spectator could interpret the Esion graphic score differently. The symbol of an activity, for instance, could be interpreted as the activity of the performers sharpening their pencils, shading, or cutting papers. The sound of these activities was recorded by a contact microphone and then transferred to a mixer. The symbols – which represented the recorded sound through wavelength or noise – were reinterpreted by using the sounds of the radio, Kord DS on Nintendo DS, as well as a synthesizer app on Android. In addition, there was the sound recorded by Milisifilem Anggrek a week before the performance, which consisted of the sound of their daily activities and conversations in Forum Lenteng. The recorded sound was selected and composed live with a mixer, intertwining with the sound of the conversations happening in the performance space.

Similar to the interpretation of Esion‘s graphic composition that is subjective, the interpretation of its sound is highly subjective, as well. What I mean is that the sound that the spectators heard would differ depending on their hearing distance from the source of the sound. Since I was sitting very close to the two noisy girls, the representation sounds that came from the speaker was masked by the girls’ increasingly loud voices. The noise generated by the spectators became a distortion for the electronic sound – which is usually associated as the established actor in the noise music scene.

In a discussion session after the performance, Otty Widasari (an artist and founder of Forum Lenteng) stated that noise had become part of socio-cultural happenings in Indonesia. She recalled that a Finnish sound artist, Tero Nauha, came to Jakarta for his residency in 2000. In the socio-cultural perspective, the nature of his previous workspace was different from the generally communal one in Jakarta. Jakarta’s soundscape together with the constant noise in his residency place made it almost impossible for him to find a sterile sound environment like his homeland to work.

From Otty’s story, this artist was then determined to provoke the noise by creating an organization of sounds, which is arranged from low sounds to extremely loud ones that could dominate and get people to be quiet. According to Otty, the brilliance in Tero Nauha’s work is that he managed to take an unruliness and turned it into a tough rule and discipline. On the other hand, Otty remarked that Esion – in contrast to Tero Nauha’s work – framed and created a composition out of the noises they found. Both provocations and critiques of a particular soundscape were presented using two different methods, and both referred to two different socio-cultural scenes, yet they equally elicited a wealth of aesthetic experience.

In engaging with the discourse of noise, I studied the literature on the genesis of noise in the arts. In Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noise (futurist manifesto, 1913), noise art is initially a critique towards sound art–which according to him, is obsessed with pure sounds, soft and clear, and always revolves around the melodic composition. So, noise through the mix of shrill and harsh sounds is to provide a disharmony in music.

However, not all noise art and its disharmony are a critique. One spectator of the performance commented that seeing a noise performance was not different from seeing a classical concert. The spectators of the noise performance still turned silent and solemn as if they did not dare to disrupt the noise’s present moment. The noise itself became established.

Esion – reversing the word noise – possesses a playful character that has transformed into an act of brilliance. The word reversal itself distorts the word noise. That particular act too is an aesthetic construction that experiments with the meaning of noise. The performance used a noise – a distortion generally produced by electronic devices – and deliberately paired it with the distortion of conversations noise. Having often been silenced by the conventions of watching, disruptive voices and sounds are now framed and composed as an artwork.

In one single action, Esion‘s performance disrupts two established structures: noise and spectatorship. In relation to the tradition of watching that I mentioned earlier, distortions in performance are methods to invite spectators to be an agent who critically constructs the performance aesthetics. The culture of watching in performance art and cinema, like other cultures, is born out of a consensus, which was made in a particular location and applied to another location. This particular culture of watching, through a long journey of time, has mutated into a new consensus in its new location. However, it does mean that the other form of culture of watching has diminished. The other culture becomes the culture of the quotidian and since the masses tend to find its fluidity appealing, it exists in the popular realm. This culture too can be viewed as another consensus that particularly orients itself towards entertainment.

With its noise performance, Esion unites these two consensuses on watching. The sacredness of watching a performance of art is disrupted by an aesthetic framing that activates its spectators so that they could choose to engage with the work, it makes the space fluid. Instead of limiting themselves as the consumers of entertainment, the spectators’ acts in Esion, such as talking back to the performers, commenting, and even participating in making noise, demonstrate the agency of the spectators. It creates a critical dialogue on the tradition of watching. At one point, the interactive process and the interpretation of everyday sounds in the performance allowed its spectators who were before unfamiliar with the concept of noise to familiarise themselves with such a concept.

Towards the end of the performance, the early noise created by the two girls was succeeded by the noise of the spectators. Even the spectator who had previously hit these girls had participated in the performance near the end. She yelled, “seize the production tools!”.

If her initial strong reaction is a sign of her not knowing, then her second reaction indicates that she is totally aware of her presence as part of an event of aesthetic experience with discursive value. She, with her total awareness as a spectator, participated in the event and seized the tool that produced the discourse. This time, it was done with full certainty that her yell would not provoke a Sssttt! from other spectators during the performance. *